Kicking and Streaming: Netflix Cannot Win

In an Ever-More Crowded Market, the Originator of the Streaming Model Is Going the Way of Blockbuster Video

Kicking and Streaming is a new series of essays surveying the state of the on-demand streaming model of media delivery and profiling the major players in the streaming service arms race. It seems appropriate, then, to begin with the model’s originator: Netflix. In short; I think they’re doomed.

Do you remember the first thing you ever watched on Netflix streaming? I do. It was the Producers remake with Matthew Broderick, Nathan Lane, Uma Thurman, and Will Ferrell. We saw it at my Aunt and Uncle’s place in Florida on my cousin’s XBOX 360. There was a limited catalog, the resolution wasn’t great, and it buffered a handful of times but it was hard not to be impressed. It's hard to explain to young people how much of a sea-change the advent of stable feature-length streaming video was when it came on the scene. Ten minutes was basically the upper limits of runtime on YouTube, LiveLeak (RIP), or EBaum’s World (somehow still alive). Now all of a sudden I can have a movie beamed right into my living room? No DVD, no player, no nothing? Sure I can only watch The Green Hornet with Seth Rogen but they’ll add more stuff soon, I’m sure. And lo and behold they did.

How a Good Deal Went Bad

Convenience is obviously one part of the streaming equation but the other (now long forgotten) half of it is what a great economic proposition Netflix streaming represented when it first came onto the scene. For a nominal monthly fee you could access a constantly-updating library of movies along with the odd TV show. The at-home film consumer was likely spending more at Blockbuster or Hollywood video and getting less out of it. Y2K nostalgia has endowed the post-streaming generation with an inexplicable affection for Blockbuster, but I can assure you, young reader, you weren’t missing much. Sterile interior design. Apathetic employees. Poorly maintained discs and tapes. Crappy selection (oh wow they have both Two Headed Shark Attack and Mega Shark Versus Crocosaurus, decisions, decisions). Plus a corporate policy of puritanism towards anything that might get Tipper Gore’s dander up. God forbid a grown adult should want to rent a movie made by some foreign (or domestic) pervert and assess its merit on their own.

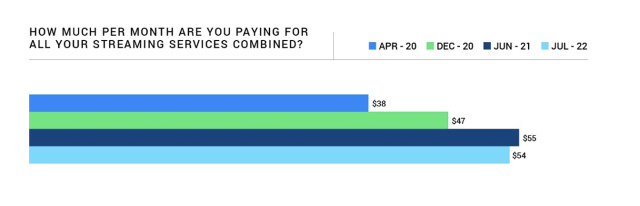

I think it’s fair to say that as the streaming market fills up more and more with name-brand platforms the value proposition once represented by Netflix has long since vaporized. Competing interests have divided the pie of “things people actually want to watch” to the point where the only logical solution is to expand the pie. It’s a pithy modern truism that streaming has basically segmented to the point of just becoming cable TV. But even with the noxious greed and monopolistic practices of the cable companies, at least hi-end cable TV packages used to give you everything. Now even with the ultra-deluxe thousand channel package you’ll still need Peacock if you wanna watch soccer, or pro-wrestling. Plus Apple TV+ for some baseball games, plus MLS. May as well throw ESPN+ on top of that for UFC and the alternate Monday Night Football feed. As more and more streaming services become “essential” for other hobbies and interests, at what point does Netflix become superfluous within the average streaming client’s monthly budget?

The “Mad Prophetic Raving” Portion of Tonight’s Entertainment

Streaming isn’t becoming cable. It’s eating cable, along with everything else. The streaming economy is tearing through all existing video media like a swarm of locusts, levying a steeper and steeper monthly tariff on the end user. Everything is within its own little walled garden now. Every brand has their own little fiefdom. The convenience and value represented by early streaming have inverted. Now it’s functionally impossible to consume even half of what the studios insist on referring to as “content.” You basically need to treat streaming media consumption as your second job to even begin to get your money’s worth from paying for it all.

I just don’t think it can go on like this. Something’s gotta give. Inflation crunching down on our budgets, looming threats of recession, unreliable viewership statistics, Hollywood labor unrest, and increasing anti-consumer practices from the streaming companies themselves are a volatile mix, to say the least. If there’s a streaming bubble, then there will be a streaming crash.

Sometimes you can just feel the storm coming on the wind. I feel there is another shoe about to drop, and I would like to suss out who may be standing under it.

The Money Fight Is Rigged

If I had to slam down money on the table and make a bet right now as to which of the major streaming platforms would go bust first in the event of a genuine crash it would be Netflix. That’s a damn shame, too. They were the innovators of this whole thing and deserve better for it. They were the first to see the potential in subscription streaming and the first to see that original, in-house content would be the x-factor once the market got crowded. Their continued hold on the culture is evidence of how successful their strategy has been up until this point.

But the indisputable fact is this: they are a venture-capital backed upstart firm embroiled in a money-fight with several of the world’s richest and most powerful corporations. This is the crucial advantage services like Amazon Prime Video and Disney+ have over Netflix. They can afford to operate as long-term loss leaders while their parent companies’ other revenue streams pick up the slack. Netflix stayed competitive by spending money virtually as fast as they make it. Evidence of the inherent volatility of this strategy has presented itself in their recent rounds of layoffs. These staffing cuts are understandable given the pure brutal economics of the situation but frankly gross from an optics standpoint. When the outlook was rosier (or at least projected rosier) Netflix was snapping up young artists of diverse backgrounds by the hundreds to bring their voice and perspective to their platform. This initiative was highly publicized and praised but when the quarterly figures were less than brilliant guess who was first to be shown the door? Some people weren’t even in their jobs for six weeks. That doesn’t just look cruel and unusual, it looks stupid. Like the right hand does not know what the left is doing.

Netflix is very quick to inform you that they are, in fact, profitable. But a closer look reveals that this is due at least in part to some creative accounting. As the streaming arms race grows hotter, bigger and riskier bets need to be placed on new and expensive projects to keep Netflix appealing to subscribers and competitive with competitors. A mix of outsider investments and subscription fees reimburse the company for their expenditure on the project. But here’s the thing, they can’t pay it all off at once. That’s just not feasible. Making even the cheapest feature films is the business of placing $20 million dollar bets. This figure can be multiplied many times for blockbuster films such as 6 Underground or The Gray Man, employing big name directors and movie stars. Furthermore, keystone Netflix properties such as Stranger Things, Black Mirror, and Bridgerton can run up similarly massive bills making just one episode of television. World-class visual effects cost money. Period-appropriate set dressing and costuming costs a lot of money.

The Two A-Words

Netflix can present itself as profitable only because it amortizes the costs of these projects over years, breaking multi-million dollar ventures into more manageable payments made over the long term. But here’s the thing; there’s always gonna have to be another project, another next big thing. If one of those (or several in short succession) fail to capture the public’s imagination, it’s very easy to imagine a feedback loop forming. Underperformance of expensive new projects leading to a stock-sell off, leading to a liquidity crisis at Netflix, which they may combat through lay-offs and project cancellations, this may incentivize more investors to sell their positions and subscribers to drop the service in protest of the cancellations, leading to even lower liquidity at Netflix and so on and so forth until they simply cannot afford to keep the lights on.

Now I am not an accountant. Netflix employs many accountants, I am sure. These people are likely intelligent and responsible and can see the same things I can see. Amortization of expenditures over a period of years is not some loophole only Netflix is crazy enough to exploit. It’s used in all sorts of industries. It’s entirely possible that they’re behaving in a perfectly fiscally responsible manner. But I would draw attention to the simple fact that all of this is ascribing a lot of responsibility to and assuming a lot of ethical behavior on the part of a company with so much incentive to lie. There is no independent ratings service to validate the self-reported viewership numbers of streaming services. They can use whatever methodology they want, and have all the incentive in the world to report that they’re constantly smashing their own records to keep investors happy. There’s precedent for this sort of thing, after all. Remember Facebook’s infamous “pivot to video?” Netflix may be inflating their own successes without doing anything illegal. You don’t need crime or malfeasance to run a company into the ground. Like Blockbuster before it, Netflix may simply be in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Garbage In; Garbage Out

The economics of the situation are plain but I think it’s underreported how the culture may be shifting against Netflix. As with all cultural reporting this is mostly conjecture, so bear with me. A lot of “I think, I feel, I’ve heard” can quickly descend into the immaterial so allow me to start with a fact. Netflix is beginning their long-anticipated crackdown on account sharing, which will no doubt win them no friends among the dorm room dirtbag class which so eagerly hoovered up every new season of BoJack Horseman and Big Mouth in one sticky, eye-aching sitting. But there’s a more ambient resentment. The focus on producing original content which drove so many eyes to Netflix has also frustrated their clientele. News of a Netflix adaptation is increasingly met with groans from fanbases of an existing IP, especially animated properties.

I don’t think I’m alone in feeling that Netflix’s original productions in recent years have somewhat deemphasized quality control as a guiding principle. Not that there’s anything wrong with that. I’m generally in favor of channeling the Roger Corman playbook to make movies or TV on the cheap. I’ve never seen the Kissing Booth movies and probably wouldn’t be able to summon up the energy to hate on them and their various cost–effective cousins even if I had. Let the kids have their fun, I say. But that’s fiction. Low-rent, low-brow, low-effort media trading on cheap emotional manipulation and well-trod tropes is all well and good when it’s just pretend. But when we flatten real tragedy happening to real people into commodified “content,” I get uncomfortable. True crime’s modern ascendancy within the pop culture content machine is exactly the kind of wholly amoral flattening of reality into commodities that gives me The Fear about the whole streaming model.

Let me be clear; I’m not a prude about True Crime. In fact I’m a sucker for well-made, well-researched explorations of real-life criminal narratives (I have a particular weakness for cults and conspiracy). Netflix has even shown a capacity to create these kinds of documentaries in the past. But let’s not pretend all of this stuff is grandfathered in to some noble tradition stretching back to Truman Capote. The recent spate of serial killer and other true crime content (across all streaming services) has been a race to the bottom. Well-thought-out perspectives, meticulous research, and relationship-building with victims and survivors take time. The imperatives of the content economy no longer allow this time. Filmmakers need to shoot their interviews, edit their b-roll, splice in their interminable animated segments and get a product to market. Period. There’s no interesting angles taken or challenging conclusions drawn in despicable nonsense like Netflix’s recent Waco: American Apocalypse. We’re not standing at the graves of murdered people, paying our respects. We’re snorting their ashes, hitting rim-shots with their bones, and splashing around in puddles of their blood. More bodies, more victims, more gruesome, more painful. If it bleeds it leads.

Conclusions: The Santa Clarita Diet Effect

Allow me to pose some questions: which was your Netflix show? You know the one. The one that you thought was simply brilliant, incredible. Reviewed very well. Gone before its time, never to be heard from again. For many people it was Sense8, for my friend from work it was Santa Clarita Diet, for me it was Neo Yokio (we’ll always have the Christmas Special I guess). Maybe you’re lucky and your Netflix show is Stranger Things, but even that appears to be moving towards some kind of inevitable conclusion. Will you stick around once it's gone? Maybe you’re a fan of Bridgerton, but is there any unique virtue there that will keep you coming back for it instead of other period romances on competing platforms? Do you actually like Wednesday, or do you just like Jenna Ortega? In a modern content economy defined by impermanence and disposability, where every big thing must be surpassed by a new, bigger thing, how long until the content delivery mechanism itself becomes disposable? Do you have any affection for Netflix? Or are they as replacable as the “content” they fund and promote?