The Professional Nerd is Extinct

Or: Confessions of a Wannabee Vice Staffer

When I was a teenager I used to dream about working for Vice. It wasn’t a bespoke kind of aspiration. I’d carry water, pen columns for any of the various imprints under the Vice Umbrella. I read enough of them to understand the basic vibe. There was the flagship site and then Vice News, Munchies, i-D, Noisey, and a personal favorite of mine; Vice Sports. In particular I was drawn to their venerable series of athlete profiles; The Cult. These columns were some of the first exposures to F1, club soccer, and other European sporting fixations which found any purchase in my American brain. It was the interpretation of sports through the lens of persona, narrative, culture which transfixed me. It’s a mode of engaging with sports which I have never abandoned. Statistics will never compel me like people.

Vice was “cool” and ubiquitous and more teen-boy-brain masculine than say Buzzfeed and so it became aspirational. But I could go even more general with my ambitions if pressed. Pitchfork? Sure. The Escapist? Sold. Rooster Teeth? Absolutely. IGN? Polygon? Kotaku? If I must, I suppose. Machinima? Brother I would have bitten your hand off. I knew nothing about money or economies of scale or the AP style guide but I looked at the graphic tees and devil may care smirks on white male faces on my not-quite-smart phone and knew that this was where I belonged. As far back as I can remember I always wanted to be New Media… and now it’s over. Hell, it’s been over.

It used to be hip to be square. Used to be. Kids like me could entertain delusions of leveraging a modest amount of useless knowledge and a cool, detached kind of arrogance into a career. But not just a career. Celebrity. Adoring fanbases in the hundreds of thousands. A reach and influence exceeding any stodgy, boring legacy media. Because those people just couldn't speak to us, man. They had nothing to offer the kids of the new millennium. We didn’t care about whatever boring stuff they cared about. We wanted to know about video games, and superhero movies, and cool people wearing cool outfits in cool foreign countries, and drugs, and cults, and crime, and sex. I just read The Vice Guide to Eating Pussy on a computer in the school library. I’m gonna be so ready if she lets me hit after prom.

It used to be hip to be square. Used to be. There was a moment. Now it’s gone. The people who made that moment were with it, then they changed what it was. Now what they’re with isn’t it. What is it is weird and scary to them. It’ll happen to you.

Sayonara, Sandman

The Neil Gaiman allegations served as a kind of lightning rod to ground my own thoughts on this subject. The spontaneous combustion of a figure with that sort of public profile and economic footprint can’t really help but leave us talking about him, thinking about him, analyzing him. Doubtless there are an infinite number of angles of attack, analysis, reflection, and reevaluation that one can take just working inside the man’s considerable canon. That is not my objective here. This isn’t literary criticism. I’m not interested in the work, I’m interested in the persona. Gaiman was many things and allegedly many more. One thing he absolutely was, in his day, was a poster. The man was an early power user of the then-nascent Twitter and Tumblr of the early 2010s, chopping it up with fellow celebrities and aspiring notables, responding to fan questions off the cuff. In so doing he helped pioneer the mode of discourse, marketing, and individual-as-brand performance of celebrity that we live with today. The prestige and (more importantly) the consistent, candid presence he brought to these platforms was a boon to the New Media net-hustlers of Web 2.0. An archetype that I’ll henceforth refer to as “the professional nerds.”

Gaiman is just the last and most prestigious to be chopped down for the blight growing in his branches. The oldest oak in the forest felled at long last, an epoch after the saplings in his shadow were ground to sawdust for their sins. The names have fallen into obscurity, and often with good reason, but you can conjure a few if you close your eyes and think, can’t you? Wil Wheaton. Chris Hardwick. Chuck Wendig. Chris Kluwe. Zoe Quinn. Felicia Day. Brianna Wu. Adam Sessler. Jessica Chobot. Adam Kovic. Yahtzee Croshaw. Anita Sarkeesian. Jim Sterling. Bob Chipman. John “TotalBiscuit” Bain (RIP).

They were the moment. The moment passed. Disco was the thing. Then Disco was dead. Then Disco sucked. Now Disco has always sucked, idiot. Why would you ever think it was any other way? Aren’t you embarrassed?

This Was the Time, These Were the Feelings

I have a sort of theory (more a hypothesis but that’s an unsexy word) about the way people engage with history as it happens to them. Specifically; how we resolve the contradiction inherent in current affairs becoming a part of history. How do we deal with the trauma of a moment having passed? Simple, we ignore it, shun it, mock it and act as if it couldn’t have possibly happened to us. That was someone else, wearing my skin. There is no time more foreign and alien to us than our recent past.

The 2010s have gotten this treatment. Just as the Reaganite optimism of the 80s recontextualized the free-lovin’ hippies of the 60s as a bunch of smelly, dirty, drug-crazed, troop-hating freaks, the cool kids of the New Media class have been reassessed as a bunch of perverts, chauvinists, racists, and frat boys. The humor, style, and values of the time have been assessed by successor generations and cultural movements and been declared cringe. You actually wore that Legend of Zelda t-shirt with those cargo shorts plus a bowtie, unbuttoned waistcoat, and fedora for some reason? You actually made that expression in a photograph that you knew was going to be posted online? You asked for a haircut that would make you look more like Zooey Deschanel on purpose? You said “amazeballs” without irony? Jail. No, actually, death. The arc of the universe is long but it bends towards everyone eventually getting a chance to be mean to millennials for being lame.

But at the time things were very different. In the dog days of the Obama Administration, a young, stylish, cosmopolitan America was reemerging after the ugly, provincial, neanderthal flailing of the Bush years. The jocks and preps and the PTA/Church Group moms had their time and they’d tanked the economy, killed rock and roll, and turned the whole damn country into one big Wal-Mart-cum-Megachurch parking lot. It was the age of the nerd. The Revenge of the Nerds, if you will.

Just to come up for air, here, it’s obvious in retrospect that we weren’t actually witnessing change in those years. We were rebranding, not restructuring. The new, young, hip breed of capitalist that was meant to save us all in 2010 has come around in 2025 to kiss the ring of a new conservative American president and set about pandering to the same America that the professional nerds scorned in the Obama years. The world never changes, all it does is turn.

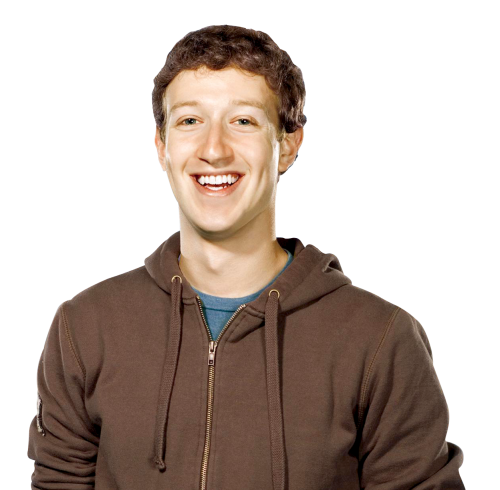

These titans of tech, the founder class, Mark Zuckerberg chief among them, were obviously at the top of the pyramid. The code-savants and system mentats in the John Carmack mould were below them. Then the venture capital types, chastened from the years of hostility after the recession but still influential and, of course, rich. But somewhere between these noble castes and the Ugly American dregs of George Bush’s America (which we were all meant to be ashamed of, see how that works?) there must be some sort of dignified existence for the artisan, right? The humble scribe, video editor, SEO jockey, webmaster. Someone needed to keep the plebs informed of the goings on of the courtier class, right? Whatever angle you approached it from, it seemed like a good business angle to inform people of what was up with these new incubators of innovation. Fashion, film, games, formless freebase culture. It all needed to be written on and opined on and fawned over and it needed to be communicated now, right now.

The avenues of communication tended towards one of two models; you had the independents and the company men. The independents weren’t really “new media” in the sense that they weren’t corporate but they fulfilled the same function. You had the YouTubers, indie bloggers, prehistoric podcasters, and, of course, seemingly benevolent independent celebrities such as Neil Gaiman. He was far from the only one, of course. Minnesota Vikings punter Chris Kluwe enjoyed a moment of professional nerd visibility when he began promoting his involvement in World of Warcraft along with pen and paper RPG’s as part of his brand. Imagine that, a pro football player who likes Dungeons and Dragons? How outrageously quirky! Wasn’t it just a trip when you logged onto Twitter for the first time in 2011 and saw that annoying Wil Wheaton kid from Star Trek: The Next Generation had grown up and could also be annoying as a full grown man?

Of course, most of the independents didn’t have the preexisting celebrity of these men. They had no insulation. They were on their own, making their videos, writing their blogs, doing their little skits. They were easy to root for in a vacuum but remember that this was a different time. Indie creators had (still have, if we’re honest) an annoying tendency to fall off the radar, go radio silent, miss deadlines, suffer unsympathetic public breakdowns. Hence the utility of the corporate outlets. While the company men and women were disposable by their very nature, there was a lot of talent hiding in those early 2010s new media newsrooms if you cared to look. That was the real beauty of New Media in its golden years. It had the dependability of TV with the underdog quality and inimitable style of the independents. They spoke our language, they cared about what we cared about. The company men would never be as beloved as the truly famous independent operators but they had their own well-being to worry about. They needed steady paychecks to make rent, needed credentials and access to inform you, the consumer. There were uncrossable lines, but did it really matter? I mean, you want to know about this stuff, right?

This was the rocket fuel that sent New Media to the moon and also the fatal flaw that caused it to burn up on reentry. These outlets and, implicitly, their employees, did not often see themselves as a traditional Fourth Estate. The idea that they were meant to challenge these new authorities of tech and culture did not often seem to be a priority. They saw themselves as aligned with many of these figures. Why shouldn’t they have been? They were all nerds after all, right? All hoodied and graphic-teed up. All eating out of the same cultural trough. When the distinction between journalist and subject blurs, “journalism” can pretty quickly be mistaken for advertising.

This leads us to the enduring question at the heart of it all; was this a work or a shoot? Were the professional nerds in on it or were they just useful idiots? Rubes with more dreams than talent who couldn’t see the other shoe dropping while they stood under it? In some cases, the answers became self evident. When #MeToo rolled around there was no shortage of freakin’ epic bacon podcasters, TV hosts, YouTubers, and “journalists” being revealed as perverts, rapists, pederasts, woman-beaters, sadists, and influence-obsessives. Painting the whole industry with this broad brush is tempting but I urge you to avoid that impulse. The true believers did exist, and when it all came down around their ears, they were the ones hit hardest. The cynics, freaks, hustlers, and abusers at least knew to get theirs while they could. The true believers, in their naivete, always allow others to go first, assuming that they’ll get their turn at the money faucet when that mythical time of plenty for all comes at long last.

Vice To Da Moon

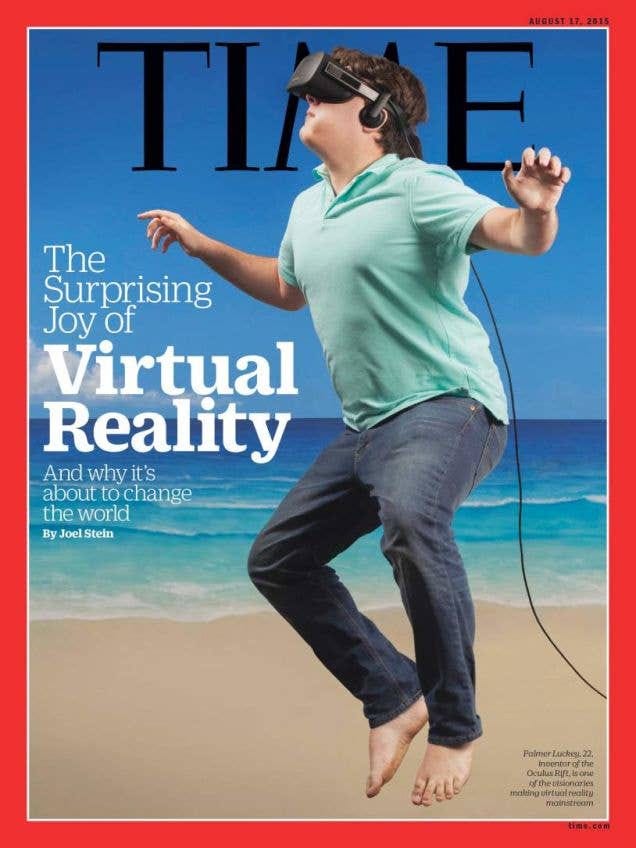

Disney was ready to buy Vice Media for $3.5 billion in 2016 and Vice’s founder and head honcho, Shane Smith, did not think that was enough. Read that again. Then consider that Disney paid $4 billion for LucasArts (a company that owns Star Wars and Indiana Jones).

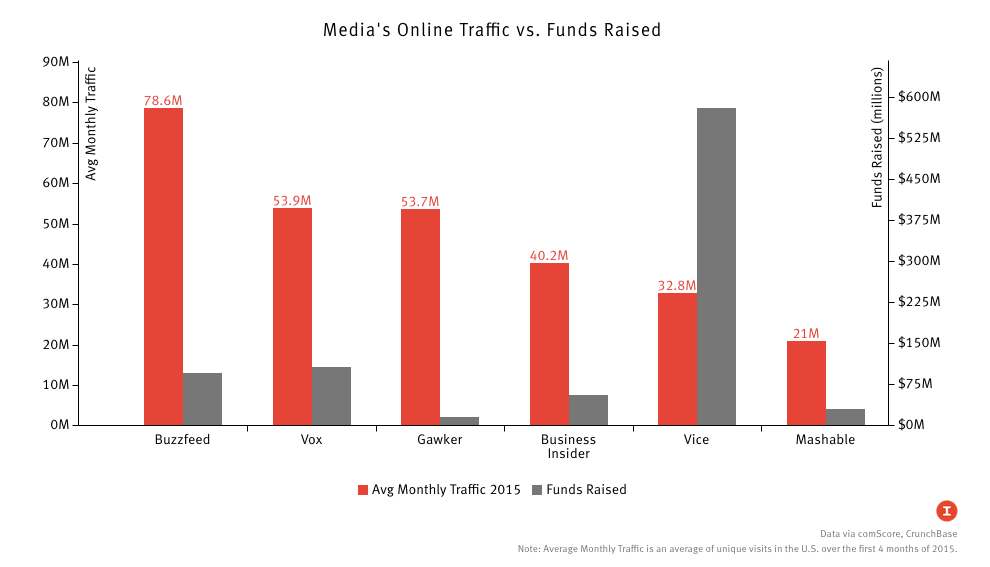

Of course it was an economic bubble. It was all a bubble. How could it not be? In fact it was a double (if not triple) bubble. There was the New Media bubble itself, wherein these companies just kept hiring new people and promoting people they’d hired, kept spinning off new imprints, kept buying expensive office space in trendy up-and-coming neighborhoods, kept throwing cooler and cooler company parties. Then there was the online advertising bubble. Think of this as upstream from new media. A large part of the reason companies like Vice and Buzzfeed grew so rapidly while remaining “Independent” is that they were able to leverage their site traffic figures to demonstrate value to potential advertisers and investors. The value of their digital real estate grew inflated for the same reasons meatspace real estate does. The people paying for these ads overestimated the value of their investment. Yeah, the go-getters in marketing that pitched this can go back to their bosses and say that they’re not prepared to call the Vice or Buzzfeed ad buys a failure because being in “cool” places adds value to a brand. However, the conclusions are obvious to anyone with sufficient perspective: like most marketing plays based on cool factor, they failed to account for the simple fact that people don’t like being advertised to and come to resent marketing as it grows more ubiquitous.

So the ad-supported business model was inefficient to say the least. Ad-buyers were growing in awareness that they were throwing good money after bad, as their investments failed to increase revenues. That’s bad in any case, but survivable. What came next was not. What made the ad space on these sites valuable and enabled them to grow, hire, pay a staff, and push their brands aggressively was a symbiosis with social media. Facebook and Twitter especially relied on New Media to draw interest to their sites. But these firms were coming of age and the model was beginning to shift. As the initial gold rush cooled, the founder class began feeling the squeeze as well. Silicon Valley’s exponential growth came about due to venture capital interests seeking yield in the wake of the great recession. Ready cash injections drove companies like Twitter and Facebook to cultural phenomenon status but once you’ve signed up everyone and their mother to your platform, how do you demonstrate growth? If you can’t demonstrate growth quarter over quarter, then why should the money men stay involved? If you can’t point to a line that’s going up then you can’t juice a stock price and therefore can’t attract new investment (which, I should mention, is also a large portion of how you compensate your employees and attract the best talent). In short: these firms were sharks. They needed to keep moving and keep devouring, and it just so happened New Media was fattened up for the kill.

With user growth slowing as social media conglomerates abandoned their status as disruptors and came more fully into the role of referees of culture and communication, the natural next step was to remove the competition and monopolize the attention economy. You can’t conjure more users out of thin air, but you can make the users you have spend more time on your platform. Like the labyrinth of Greek myth, the algorithms that shaped social media began to rearrange the walls, rewrite the rules, show some things more and others less, sometimes they informed you of these changes, sometimes they did not. Slowly, slowly, and then all at once, New Media found themselves deprived of the strong traffic, the attention of the public, which had been their trump card. The result was a doom loop. Less traffic means less valuable ads means less revenue means reduced resources for new and exciting content to attract readers and viewers which means less traffic and so on. Social media shivved one of their strongest allies in shaping the character and complexion of Web 2.0, robbing Peter in Brooklyn to pay Paul on Wall Street. We didn’t fully appreciate what a heel turn this was at the time. Now I don’t think we have any other choice. We’re living in the Silicon Valley Kaliyuga. The bad tweets are coming from inside the White House.

Somewhere in the World is the Most Cringe Man

The “professional nerd” didn’t so much disappear as it was transmogrified from one thing to something very different. The sorts of jobs I aspired to as a young Vice reader still technically exist but they’re few and far between. Worse yet, the atrophy of New Media as an economic force had made its remnants even more captive to capital. The independents still exist and still do good work but they’re not what they once were either. Not everyone can grow a brand from zero, and I don’t think that’s any great sin. Frankly I forgive people who grow discouraged. The barrier to entry in terms of presentation and professionalism if one wants to stand out on YouTube, Twitch, or (naturally) Substack has never been higher. This is before we even discuss how precarious that existence remains, even once the aspiring independent creative achieves that mythical critical mass of attention and can go “full time.” The margins remain razor-close even once you have an audience of children who think you’re a rich, famous, important celebrity. The career path has rapidly lost viability, leaving only empty aspiration, methadone for a generation staring down an eternity of spreadsheet toil and post-AI obsolescence. One day, you can tell yourself, one day you’ll buy a proper microphone and write that video essay detailing how you’d fix the Star Wars sequels.

Like so much else in modern American life the ladder to dignity, prestige, and full economic personhood has been pulled up by the plutocrat class, who of course feel no compulsion to be realistic or live within their extravagant means. The twentysomethings who were saving the economy in 2010 are now fortysomethings with failed marriages, pathologies, and all the nerd insecurities they possessed as college dropouts with big dreams. If you want an example of a true cynic taking advantage of an optimistic time, look no further than Elon Musk. His rise from the moneyman court eunuch class to the realm of tech founder philosopher kings was built on bought-and-paid for good press from professional nerds of all stripes. Cameos in Star Trek, The Simpsons, and the then-nascent Marvel Cinematic Universe. Social media friendly puff pieces about epic science man Elon. Even the branding move of co-opting noted smart guy beloved by dumb guys Nikola Tesla feels like a purposeful attempt to court the sort of tech-optimist millennial set held in the thrall of new media and, by proxy, big tech.

It was in this way that New Media and the Professional Nerds which made it work let the foxes into the hen house. They ignored the obvious flaws in their benefactors out of a mistaken sense of commonality. A sense that what they were like was secondary so long as what they liked was the same. That’s the thing about liking things, though, eventually you get bored of it. You move onto something else. Identification with commodities never ages gracefully, lots of people with band tattoos they regret twenty years hence. So it was with the Professional Nerds. They were paid to be with it, then they changed what it was.

A problem also is that you *can* get attention by being a hipster nerd or whatever:

But it turns out you can *also* get attention with any stupid slop: cooking asmr, ai anime girls, family guy clips, whatever. So why would advertisers pay higher rates for a real website with a budget when they can just pay Pennies on YouTube or pay Facebook for super micro targeted stuff?

really great fucking piece holy shit. i too would have loved to be a professional nerd. wonder who’s still hiring those kinds of jobs?